Strawberry Angular Leaf Spot

Angular leaf spot is a sporadic but potentially serious disease of strawberry in Wisconsin. Our relatively cool climate, especially nighttime temperatures near freezing, is conducive to disease development. Angular leaf spot is caused by a bacterium (Xanthomonas fragariae), which distinguishes it from other strawberry diseases in Wisconsin, most of which are caused by fungi. As such, angular leaf spot cannot be controlled with the fungicides commonly used on other leaf diseases. Accurate identification of angular leaf spot is important so that appropriate control measures can be taken.

Identifying angular leaf spot

As the name implies, angular leaf spot affects leaves, which leads to decreased plant vigor. However, direct yield losses occur when the infected calyx (leafy fruit cap) becomes black and dry or when peduncles (fruit stems) are diseased. Symptoms vary depending on how long the disease has been developing and on weather conditions. Anecdotal evidence suggests that symptoms also vary among cultivars (e.g., certain cultivars may be more prone to calyx rather than leaf infection), but this has not been well documented.

Leaf spots first appear on the lower surfaces of leaves as tiny, water-soaked lesions that are delimited by veins (Figure 1). The angular spots appear yellow to pale green and translucent when held up to light, but dark green and opaque when viewed from above. Under wet conditions, a slimy white film, which consists of masses of bacteria, oozes from the spots. Upon drying, this film becomes scaly and can easily be scraped from the leaves. As the disease progresses, spots become more numerous, merge, and become visible on the upper surfaces of leaves as reddish-brown dead areas (Figure 2). The edges of leaves may appear ragged as dead tissue breaks off. At such advanced stages, angular leaf spot is difficult to distinguish from fungal leaf-spotting diseases (e.g., leaf blight, leaf scorch, and common leaf spot). Therefore, it is important to scout for angular leaf spot when leaves still look healthy. Be sure to look at the undersides of leaves to detect symptoms at their earliest stages.

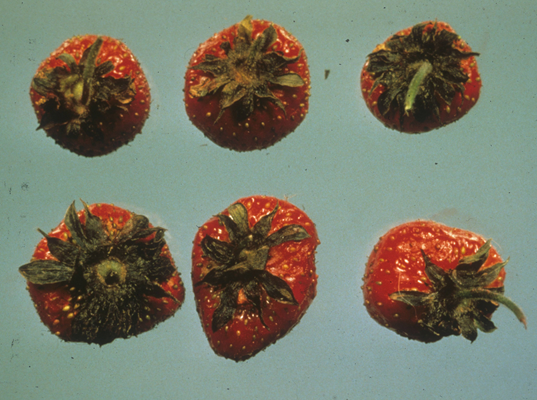

An infected calyx initially appears dark green, water-soaked, and limp, but then it quickly dries and turns black (Figure 3). Usually if the calyx is diseased, the peduncles will also be dark and wilted. Usually the berry flesh is not affected, but the blackened calyx makes the fruit unmarketable. X. fragariae can become systemic, affecting vascular tissue in all parts of the plant including the crown and roots. Severe infection of the crown can cause sudden wilting and collapse of the plant, although this is not a common occurrence in Wisconsin.

Disease origins and spread

X. fragariae is introduced into commercial plantings on infected but healthy-appearing plants. While most nurseries take measures to control angular leaf spot, they often cannot eliminate the pathogen. In established plantings where angular leaf spot has occurred, the pathogen can overwinter in infected leaf debris and persist in plant crowns. X. fragariae apparently does not survive on plants other than strawberry. Disease development is highly dependent on the environment, although the precise conditions required for angular leaf spot are not known. Angular leaf spot is favored by cool to moderate daytime temperatures (65-70 oF), cold nighttime temperatures (near freezing), high relative humidity, and wet conditions brought on by rain, irrigation, or heavy dew. In Wisconsin these conditions are very common during May, coinciding with the development of vigorously growing tissues that are highly susceptible to angular leaf spot. Nevertheless, this disease sometimes is absent or goes unnoticed early in the season but then quickly develops after rainy periods later in the summer, especially on new growth after renovation.

After symptoms develop, bacteria in a slimy white matrix ooze from stomata (breathing pores on leaves) onto the leaf surface. From there the bacteria are easily splashed about the planting by rain or irrigation water. The bacteria-laden slime can also get carried across a field on equipment or feet. X. fragariae infects strawberry tissues through stomata and perhaps hydathodes (small openings on the margins of leaves) and tiny wounds caused by abrasion from blowing sand.

Control

As with any disease of strawberry, control begins before you put the plants in the ground. Bacterial diseases, however, are notoriously difficult to control. Unlike fungal diseases for which there are many effective fungicides, angular leaf spot is difficult to control by spraying. Nevertheless, there are things you can do to minimize losses from angular leaf spot.

- Site. Choose well-drained sites with good air circulation and exposure to sunshine. This will minimize the time that plants are wet and should reduce the incidence and severity of all diseases.

- Rotation. Because X. fragariae survives in leaf debris, do not establish a new planting in soil containing old strawberry leaves, especially where there is a past history of angular leaf spot. If you are on a 3- to 4-year rotation with other crops, this should not be a problem because once leaf debris decomposes, the pathogen cannot survive in the soil.

- Weed control. Control weeds and maintain alleys between rows to improve air circulation.

- Nitrogen. Use nitrogen fertilizers sparingly. The soft, succulent tissues that result after heavy nitrogen application are especially susceptible to angular leaf spot.

- Copper. Copper-based fungicides (e.g., Champ, Kocide, COCS) and newer copper-based products (e.g., BadgeX2, Cueva, Magna-Bon) have shown various levels of control in trials. These may help prevent infection of new tissues when the pathogen is splashed about, but they will not control growth of bacteria that are already inside plants. To prevent new infection, copper-based products should be applied as early in the spring as permitted on product labels, when plants are rapidly growing. The main purpose of springtime sprays is to prevent infection of the calyx, which can make fruit unmarketable. When re-growth occurs after renovation, the benefits of copper are questionable. At this point the weather is usually not favorable for angular leaf spot, and it’s not clear that leaf injury from angular leaf spot is economically important. Unfortunately, copper can be toxic to strawberry leaves after 4 to 5 applications. If this occurs, quit using it—the risks outweigh the benefits at this point.

- “Soft” chemistries. Copper-based products are the most-tested for angular leaf spot control. However, in trials in Florida, the plant resistance activator Actigard has shown some efficacy. In one report from Michigan where disease pressure was low, Regalia, Serenade Optimum, and Double Nickel controlled angular leaf spot. I am not comfortable recommending these products, however, because very little research data has been reported.

- Cultivars. Unfortunately, cultivars highly resistant to angular leaf spot are not commercially available. The most popular cultivars in Wisconsin, including Annapolis, Cavendish, Honeoye, Jewel, Kent, Sable, and Winona, are all highly susceptible. Tristar has shown tolerance (gets symptoms but without much impact on the plant) to angular leaf spot in Wisconsin.