Biological Control Part I: Integrating Biological Control into an IPM Program

Biological control involves the reduction of pest populations by natural enemies (including predators, parasitoids, pathogens and nematodes) due to human intervention. In this article (Biological control Part I), we will consider different types of biocontrol strategies and discuss the advantages and difficulties of integrating biocontrol into an IPM plan. In the next issue (Biological control Part II) we will introduce the many effective natural enemies that are found in Wisconsin.

Biological control can be divided into three different strategies: importation, augmentation, and conservation biocontrol. Each can be useful in certain situations. Importation biocontrol, also known as classical biocontrol, is used when trying to control an invasive pest. The idea behind importation biocontrol is that invasive pests are often only prolific and problematic because they are outside of their native range, and therefore do not have natural enemies in this new range to control their populations. Therefore, by importing biocontrol agents from the pest’s native range, the invasive pest’s outbreak sometimes can be kept in check. A concern with this strategy is that the imported biocontrol agent, if it is a generalist feeder, may also feed on our native insects or become a pest itself. For that reason, importation biocontrol requires a great deal of research and time, to determine which potential importation biocontrol agents will be most effective at controlling the pest species, without causing any adverse effects.

Augmentation biocontrol involves rearing and releasing a biocontrol agent to increase (augment) the existing natural enemy populations. In general, these releases need to be made regularly, like a pesticide application, to continue to maintain control year after year. Some natural enemies commonly used in augmentation biocontrol include ladybeetles, parasitoid wasps, and predatory mites. Augmentation biocontrol is most often used in a greenhouse or other controlled environment, and, in those situations, can be a very effective way to limit pest populations. However, for augmentation biocontrol to be effective, you need to be sure to correctly identify your pest of concern, release a biocontrol agent known to work against the pest present, ensure the timing is right for them to be most useful (at the optimal life stage and density of the pest), and provide the conditions (habitat, shelter, food availability, environmental conditions) necessary for these biocontrol agents to survive.

Providing the best conditions for natural enemies to thrive is also the key ingredient in conservation biocontrol, which involves altering the agro-environment to provide the best conditions for naturally occurring, native biocontrol agents to thrive and be most effective. Some common tactics in conservation biocontrol include providing floral resources for nectardrinking biocontrol agents, providing hiding and nesting spaces along field borders, and minimizing pesticide application that may have a non-target effect on biocontrol agents. Conservation biocontrol has its own set of challenges, including that it can be more complex or time-consuming to implement, recommendations may be somewhat general, and some research in this field has focused on academic questions rather than practical recommendations. However, many of the tactics for conservation biological control also benefit pollinators, and the cost and time to implement them can often be offset by government or private grants.

How to incorporate biocontrol with other IPM practices

Biological control can be one of the most cost and time efficient pest control strategies. However, it does require an understanding of the pest/predator interactions and of the unintended effects of your other farm management practices.

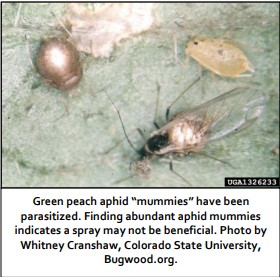

The first cornerstone of most IPM programs is monitoring of pest populations (as was discussed in the first installment of this series). When incorporating biocontrol with monitoring, it can be helpful to monitor also for natural enemies, and to adjust the economic threshold for when to spray according to not only the prevalence of the pest, but also the abundance of natural enemies. For example, when scouting for aphids, calculating not only the number of aphids but also the number of parasitized aphid “mummies” can give an idea if natural enemies are likely to control this pest on their own in the near future, which may mean that spraying is not only unnecessary, and thus a waste of money, but could also do more harm than good by decreasing natural enemy populations.

Fruit crop production has an inherent advantage in terms of maintenance of biocontrol agents, since the typically perennial nature of these crops promotes habitat stability, which generally also supports natural enemy populations. Some cultural control methods, such as the use of mulch, have been shown to further encourage natural enemy abundance and diversity. Unfortunately, other control methods can have a negative effect on natural enemies. Sticky traps and insecticide applications may have non-target effects of removing natural enemies alongside pests. However, it certainly can be possible to overcome these difficulties, and to incorporate biocontrol with chemical and other controls. One important strategy to minimize these non-target effects on natural enemies is the development of more selective products, which remove pests but do not target beneficials. Additional strategies to protect natural enemies (as well as pollinators) when using pesticides include spraying at a time and location when beneficials are least likely to come into contact with the pesticides, spraying only when necessary, and, when possible, and focusing spray applications on limited areas where the pest is most likely to be most prevalent (i.e. field edges).

By using these strategies, biological control can be successfully incorporated into an IPM program to help provide effective and cost-efficient pest control, even in places and at times when other control methods cannot be used. In the next issue, we will discuss the different species of natural enemies present in our orchards, marshes, farms, and vineyards.

Much of the information for this article came from the following resources:

Orr, D. (2009). Biological control and integrated pest management. In Integrated Pest Management: Innovation-Development Process (pp. 207-239).

Springer Netherlands. Dreistadt, S. H. (2014). Biological Control and Natural Enemies of Invertebrates: Integrated Pest Management for Home Gardeners and Landscape Professionals. University of California, Davis, Agriculture and Natural Resources.

This article was posted in Insects and tagged IPM.