Cranberries: Frequently Wondered Questions in Frost Tolerance

These might or might not be the questions everyone wonders about cranberry frost tolerance as buds break dormancy in the spring, but they had been mine, so maybe they’ll help you as well. I grew up with “The Frost Tolerance Chart” tacked onto the wall, but I was in middle school, so I didn’t read the paper. Talking with growers about frost tolerance heading into this cold weekend encouraged me to take out the paper and connect the dots.

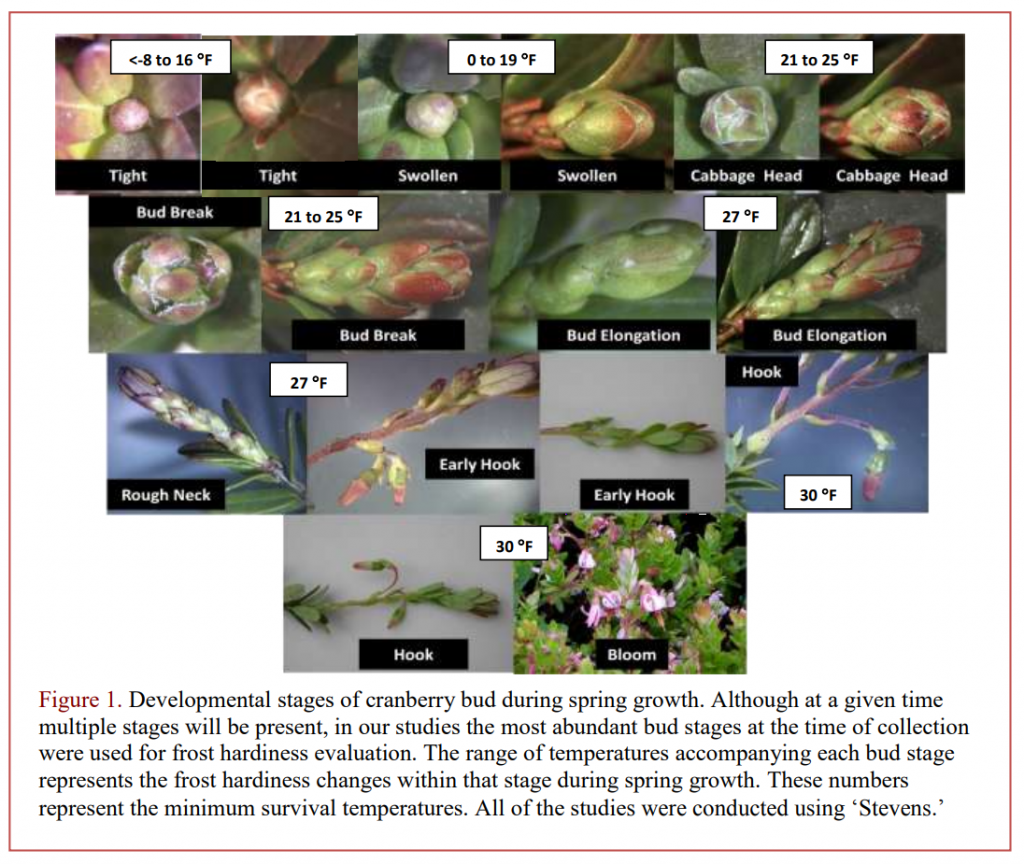

My biggest question as a twelve-year-old, was about the huge jumps. When can a tight bud tolerate -8°F, and when should it be protected at 16°F? It turns out this was a big question as they were performing the research, too. To understand that range, let’s look at how they ran the experiment.

They clipped Stevens uprights with buds on 21 days, through all 9 growth stages. They chilled the uprights in a glycol bath, precisely controlled, to 10 different temps. The 10 temps they used changed based on what we already know about bud tolerance: for tight buds, they tested temps between -4°F and 32°F ; while for bud elongation they tested from 24°F to 32°F. Then after exposing the uprights to these lab-controlled frost nights, they watched how the uprights recovered and continued growing. The research marked the temp at which 50% of the uprights were impaired (that is, 50% were killed or 50% of the tissue was damaged).

Now for those large ‘tolerable ranges’ for tight buds and swollen buds. There were tight buds in their samples on 14 of the 21 sample days—every sample between April 15 and May 28 (1997) was more than 30% tight buds. The first 5 sample days, the buds were fully dormant—even at -8°F, they weren’t damaging 50% of the uprights. By the 6th sample day, some buds had swollen, but more than 50% of the tight buds were still surviving -8°F. On May 9, 50% damage was reached at +8.4°F. (Swollen buds on the same day were damaged at +6.9°F). Across the next 7 sample days, the tight buds gradually became less and less tolerant—on May 28, 50% of uprights were impaired at 16°F. After May 29, enough buds were swollen or cabbagehead that growers should focus on those buds instead. So we really are seeing a big difference in the temperatures tight buds can withstand over the course of the spring. This suggests to me that more is happening within the bud than we can see just by watching bud stage.

Swollen buds tell a similar story. Swollen buds made up more than 10% of the samples on 11 days—between May 5 and June 1. Across these days, we see swollen buds becoming 50% damaged at -0.8°F on May 5; and swollen buds becoming 50% damaged at 18.7°F on June 1.

The huge ranges on “The Frost Tolerance Chart” really do represent exactly what the research found—that you can see a tight bud, or you can see a swollen bud, or you can see a cabbagehead—and that information by itself is not enough to tell you when to frost protect. You need more information: depending on the length of time since ice-off, depending on your pattern of air temperatures, and accumulated heat, and possibly even day length—your cranberries will be more or less vulnerable to dropping temperatures.

Another question I’ve wondered: this research was done with Stevens, a very popular and widespread variety—and also a very durable variety. Now that we have more than a dozen varieties popular among growers—many of which are earlier, or more “racehorse-y” varieties than Stevens—should we start to ask if we want to consider these varieties as we set our sprinkler switches? One possibility is that all varieties are “the same when they’re at the same bud stage.” But given what I know about how many factors impact bud sensitivity—I want to ask how variety impacts it, too.

The more I dig into this research, the more I’m grateful for the immense good work Beth Ann Workmaster and Jiwan Palta have done for us already. And the more I feel curious: What’s going on within tight bud, and within swollen buds, that we might notice, if we look using more than our eyes?

Lt10 explanations from Shifts in Bud And Leaf Hardiness during Spring Growth and Development of the Cranberry Upright: Regrowth Potential as an Indicator of Hardiness