Early Herbicide Success Keeps Late Season Budget in Check

As many of you are working on or finishing up your Casoron applications against broadleaves, I wanted to share some reminders for the rest of your spring weed control. Setting up a strong offense early in the year when weeds are germinating and small can keep you within budget. The better your early treatment works, the less time and money you will spend cleaning up escapes.

Timing is critical in our spring applications. Broadleaf weeds are most susceptible to herbicides when they are actively growing, but smaller than a soda can. Annual and perennial grasses are vulnerable when they’re in phases of active growth.

Evital 5G is effective on several grasses and sedges, but also has some action against cranberry. Reduce your rates on sandy soils, or if you grow Stevens, McFarlins, or the descendents of these varieties. Sedges have edges, rushes are round, grasses have joints all the way to the ground: Poast and Select Max will work only on grasses. To reduce vine damage, do not apply during the heat of the day. QuinStar is effective against dodder, as well as some broadleaves and other grasses, but it shouldn’t be applied to weak vines. QuinStar does have restrictions from many handlers. With this and every herbicide, check with your handler for current-year restrictions before you make an application!

If you have escapes from your strong spring program, you can always fall back to your wiping defenses: 2,4-D (Weedar 64) and glyphosate (not all formulations are registered for cranberry so check the label) can be wiped on weeds while avoiding cranberry vines. These are both systemic herbicides, so you will not see damage on day 1 of application, and plants may take several days to die. It is better NOT to do tank-mixes of systemic and contact herbicides, because contact herbicides will arrest plant growth, leading to poor uptake and circulation of the systemic herbicide.

Mesotrione (Callisto) can be a useful backup for sedges and rushes as well—be sure to use a non-ionic surfactant to get the best coverage.

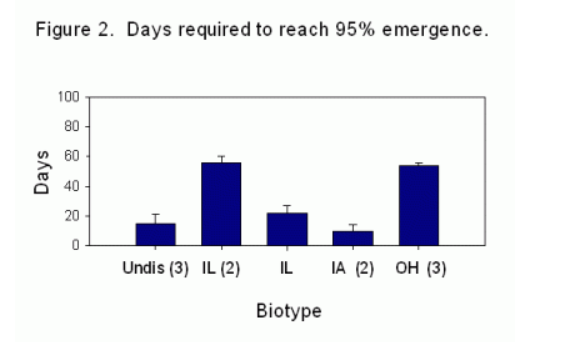

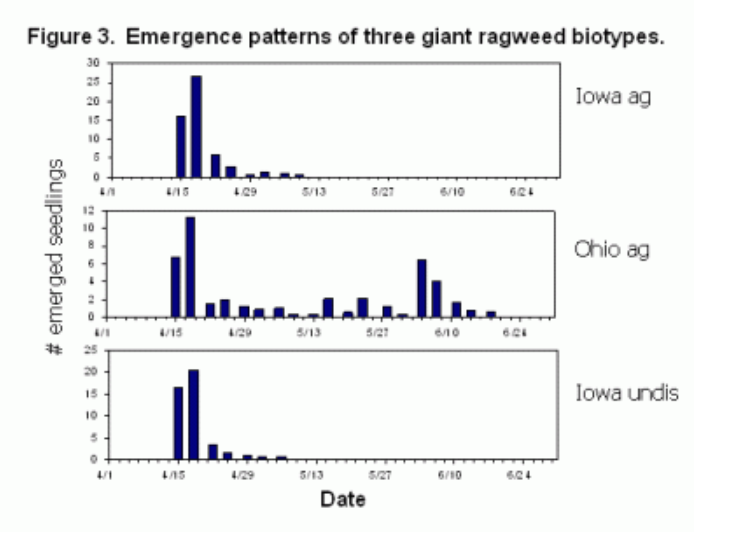

One of my favorite papers, an oldie but a goodie, compares emergence habits in 12 biotypes of Giant Ragweed to explore why G-rag is harder to fight in some regions. Some biotypes emerge over a very tight time window, and some emerge across a longer date range. People who face the wide germination window G-rag are likely to think “I didn’t get good coverage,” or maybe “my G-rag is showing resistance to the herbicide I just used,” when in fact they had good coverage and their weeds are susceptible—but new weeds emerged after the application. Anecdotally I’ve seen similar patterns from other weeds too, so I always want to remember this advice:

“There is a tendency to blame all problems in weed management on a weed’s ability to survive herbicides. This study illustrates that factors totally unrelated to herbicide tolerance can have a significant impact on the efficacy of weed management programs. It is critical to understand why weeds are able to survive management tactics.”

If you assume you know why weeds are surviving, and you’re getting it wrong—you’re going to solve the wrong problem. Take a look at your bed (after the reentry interval!) to see if your escaped weeds were damaged but survived—or if they hadn’t germinated at all—or something else!

Sources:

https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0145/8808/4272/files/A3276-2020.pdf

https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/encyclopedia/giant-ragweed-emergence-patterns

This article was posted in Cranberry and tagged Cranberries, Herbicides.