Degree Days: What They Are, How To Calculate Them, and Why They Matter to You

Degree days (DD) are a tool with which we can estimate the most abundant life stage present of a certain pest species at each point in time. This is extremely important for growing fruit crops, because it increases the efficiency of your pest monitoring and pesticide applications, by timing them accurately to when pests are most likely to be present, and thereby saving the cost and time of excessive applications while ensuring adequate pest control. In some cases, DDs are also used to track plant development, allowing growers to predict how plant developmental stages will align with calendar dates and with pest pressures. When being used to calculate plant development, they are often called “Growing Degree Days”.

How to calculate Degree Days: Degree Days take advantage of the fact that plants and insects are ectotherms, meaning they require a certain amount of heat energy to develop. Unlike you and I, plants and insects cannot create their own metabolic heat, and so they rely on external heat to allow them to grow and mature. Below a certain temperature, called the “lower developmental threshold”, the plant or insect is not developing, and above a certain temperature, the “upper developmental threshold” development slows as temperatures increase. These developmental thresholds are different for each plant or insect species, meaning that each species matures within a different optimal temperature range. The first job of a researcher is to determine the thresholds for the crop or pest of interest – this has already been done for many of the key pests affecting Wisconsin Fruit production.

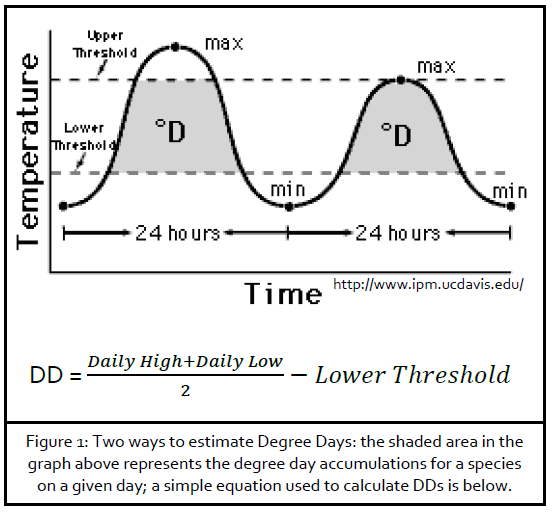

Once the thresholds have been determined, DDs can be calculated a number of different ways. The most precise calculations approximate temperature fluctuations over the course of a day with a sine wave, and calculate the area underneath the sine wave within the bounds of the organism’s temperature thresholds (see the shaded area of figure 1). An easier calculation of the number of DDs accrued by a plant or insect on a particular day is represented in the equation in figure 1. The only information necessary for this calculation is the daily high and low temperatures and the species’ thresholds. The DD accumulation for a given day is calculated by adding the daily high to the daily low, dividing by 2, and subtracting the lower developmental threshold. If the daily high is warmer than the upper developmental threshold, you will replace daily high in the equation with the threshold. Similarly, if the daily low is colder than the lower developmental threshold, you replace daily low with that threshold.

Once you have calculated the day’s accumulated DDs, you can just keep a running tally, adding each new day to the previously accumulated total. However, you do need to know when to begin tabulating DDs. For many species, there is a certain date, often March 1st, when accumulation begins for the year. For other species, DDs begin to be tabulated following a certain event, such as the first trap catch of an adult moth to calculate larval infestation.

Using Degree Days to estimate Development: Now you know how to calculate your accumulated degree days, by finding the upper and lower developmental thresholds for the insect or plant of interest, along with the daily high and low temperatures, plugging them into the equation above, and adding each new day’s DDs to the previous total. But then what does it mean? The final piece of information is to know the “degree day benchmarks”, or the number of degree days necessary for an individual to complete a life stage. This is different for each plant or insect species.

For example, for sparganothis fruitworm, overwintering larvae require around 600 DDs to develop into moths, and the moths require an additional 85 DDs to begin to lay eggs. Similar information is available for some of the most problematic pests in Wisconsin, and is in the process of being developed for others. So, as seen in the previous example, the Steffan Lab has calculated degree day benchmarks for sparganothis fruitworm (which will be reported on weekly in the Cranberry section of this newsletter), and this summer they are working on calculating benchmarks for cranberry fruitworm.

When looking at plant development, DD are often used to predict phenological stages in the plants, such as bud break or bloom, as well as harvest. Multiples models have been developed based on growing DD and other plant and environmental factors to predict when these events will happen. Michigan State University has developed and apple maturity prediction model based on growing DD that helps predict when fruit should be harvest to achieve the maximum quality during post-harvest. Likewise, peach harvest date has been shown to correlate to the growing DDs accumulated during the first 30 days following bloom.

Why Degree Days are important to you: Insecticides are often limited by the fact that not all insect life stages are equally susceptible. For example, eggs, larvae, adults and pupae of a beetle (red flour beetle) were exposed to four different insecticides

(spinetoram, imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and chlorantraniliprole). None of these insecticides were effective against pupae and efficacy of chlorantraniliprole (Altacor), for example, was greatest for young larvae (nearly 100%). Mortality was much less for other life stages (i.e. 66% for adults, 64% for old larvae, and 40% in eggs, Saglam et al. 2013). So if an insecticide application missed the time window when larvae are young, effectiveness would decrease sharply.

What’s the difference between Growing Degree Days and Chill Units in plant development? The term “chill unit” was developed to quantify how long plants need to be exposed to chilling temperatures to break endodormancy or “complete rest”. A “chill unit” is defined as one hour at 45°F. However, partial chill units can be gained or lost based on a broader range of temperature. Chill units are calculated beginning late summer. Once the temperature starts dropping in October or November, chill units will start to accumulate and from that point on a running total is calculated. Chill unit requirements to complete rest vary among fruit crops and varieties, apple trees ranges from 800 to 1700 chill units while almond range between 50 and 700 units to complete rest. After the rest has been completed buds need to be expose to a period of warm temperatures (over 40°F) to resume growth, referred to as “growing degree day” accumulation. This prevents buds from breaking too soon, when there is still a likelihood for frost damage. They have to wait until March or April to accumulate the required growing degree days (which vary depending on species). So once the plant has received both the required chill units, followed by appropriate growing degree day accumulation, buds will begin to break and flowers will begin to open up! Happy spring!

Precise and accurately timed insecticide applications can save fruit growers hundreds of dollars per acre. For example, in a study completed in apples, applications made three days early led to 1.4% greater yield damage, and applications made three days late led to 2.0% greater yield damage, than applications made at optimal timing. Optimal treatments were

achieved by timing the insecticide applications for adult trap catches of the insect pest, along with the use of a degree-day model (Sjöberg et al. 2015).

Accurately timing insecticide applications is always important, but has been especially crucial in recent years given the widely variable spring temperatures seen lately. For example, if you always spray an insecticide on May 7th, to target adult emergence of some pest, in a warm year you may have already lost much of your crop because adults emerged in late April, while on a cold year you may have no insecticide efficacy because the pest remained hidden underground as pupa until mid-May! By using DDs, you can more accurately predict adult emergence, and time the insecticide application to prevent most pest damage.

How to use Degree Days this summer: If you would like to use degree days this summer, but have not done so before, the easiest way to calculate your degree day accumulation is to find your closest weather station (go to www.wunderground.com), take the daily highs and lows, and plug them into a degree day calculator (i.e. http://agwx.soils.wisc.edu/uwex_agwx/thermal_models/degree_days). For cranberry growers, information regarding plant and pest degree days will be available on the Steffan Lab website and in this newsletter. For other fruit growers, we hope to include this information soon, but for now you should look at our website for more information on degree days.

This article was posted in Other News and Resources, WFN, Vol. 1-4 and tagged Amaya Atucha, Degree Days, Elissa Chasen, Janet van Zoeren.